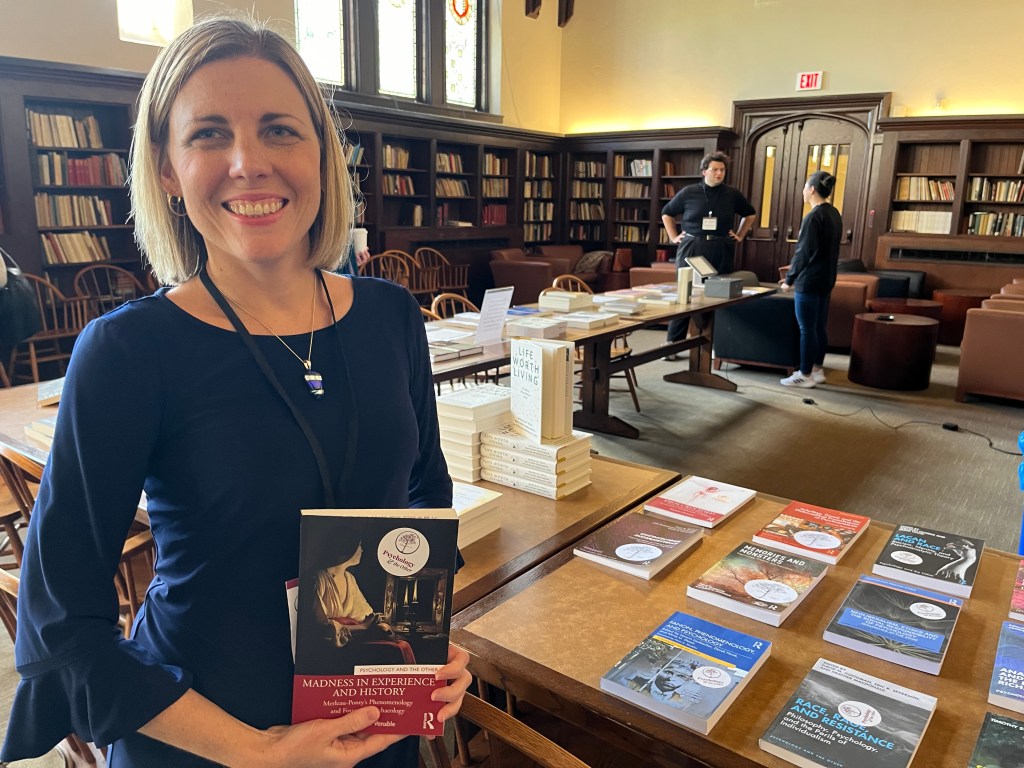

I offered two conference presentations at the Psychology and the Other Conference in Boston from October 6-8, 2023. It was a busy weekend but great conversations were had. My book was also sold at the conference. Here is a picture of me with my book at the book table.

My first paper was titled, “Practical Considerations for Schizophrenia, Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar I Disorder: Drawn from Phenomenological Experiences and Historical Structures.” It was based on Chapter 8, the last chapter in my book.

Abstract:

Many agree that philosophy can contribute theoretically to a better understanding of mental health, but can it practically help practitioners? Without denying the benefits to a theoretical framework, my explicit goal in this paper is to provide practical tools that arise out of philosophy in order to better address three disorders: schizophrenia, major depressive disorder and bipolar I disorder. I discover these tools by bringing together two philosophical perspectives: an analysis of individual experience (using a phenomenological approach) and an analysis of historical background (using an archaeological approach). The phenomenological perspective will be guided by French philosopher, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and the archaeological perspective will be directed by French philosopher, Michel Foucault.

Beginning with schizophrenia, I will demonstrate how an experience of a hallucination comes from a nonrational behavior that is shared both in hallucinations and perceptions. This shared behavior is often overlooked due to the unspoken cultural structure that labels signs of nonrationality as moral failure. What we will find is that, even though there is no longer an explicit moral condemnation of schizophrenia today, the past and present historical structures help us identify one source for unexplained feelings of guilt experienced by many patients.

In regard to major depressive disorder, I will trace the structures of the world, such as spatial and temporal structures, that patients rely on in their state of sadness, to both understand their condition and secure a path forward. We will learn that the structures that patients depend on are not just bodily structures, but also cultural perceptions of depression which have changed over time. Surprisingly, these changes are not always due to observations of the disorder but are constructed to satisfy prior qualitative systems.

For bipolar I disorder, I will map the experience of a manic episode onto a spectrum of space centeredness. Although manic episodes demonstrate an extreme relation to space, we will find that usual human experiences are based on the same patterns of “lived space” which can range from decentered to overly-centered perceptions of objective space. Due to the variety in manifestations of this disorder, a cultural analysis encourages practitioners to treat a diagnosis of bipolar as a descriptive interpretation rather than an explanation.

The motivation behind these descriptions is to give a fuller — more human picture — to experiences of illness. From his decades of work in psychiatry, Arthur Kleinman writes that practitioners must consider the “illness” of a patient, which is the “innately human experience of symptoms and suffering,” in addition to the “disease,” which only includes the ordering of theories about a disorder.(fn) Following Kleinman’s appeal, this paper helps us see illness “as important as disease” by investigating an individual’s experience of a disease and the placement of that disease in our historical context.(fn) Although the applications offered in this paper by no means replace the medical accounts, they supplement them by grounding these disorders in the wider frame of our humanness.

My second paper was titled, “No Longer Foreign: Four Phenomenological Principles Drawn from Disability Studies.” This paper came out of my class that I taught in Spring 2023 on the Philosophy of Disability.

It is a common misconception that an analysis of abnormal behavior gives us insight into normal behavior by means of contrast. In other words, we may think that if we identify the defects and problems in abnormal behavior, we can then find the opposite to be true in normal behavior. Readers of phenomenological literature can sometimes be confused by the frequent discussion of disabilities and assume that these accounts are there to demonstrate the lack of something that is then present in those without disabilities. While phenomenology does not want to do away with distinctions entirely between the normal and abnormal, its purpose in addressing disability is precisely the reverse: a phenomenological account of disability gives us insight into human behavior — not because it is foreign — but because it reveals what is shared in all human experience. In fact, it is sometimes in the so-called abnormal behavior and experiences that we are best able to identify the fundamental human ways of encountering the world.

This paper would like to contribute to the growing discussion in phenomenology that exposes these shared human patterns by exploring one area in particular of disability studies: the bodily process of adaptation and learning for those with disabilities. I will argue that as we explore the experiences described here, we will find four common principles which apply to general human adaptation and learning. First, in consideration of cases of blindness, deafness and depression, we will see how humans rely on our bodies to take in the world. Second, in reviewing cases of spinal cord injury, we will find that the development of habits is through a gradual movement from the “I cannot” to the “I can.” Third, analyzing the use of technology for mobility, such as a wheelchair, we will discover how we all incorporate instruments into our experience of the world. And fourth, by looking at experiences in disability sports, we will discuss how we all receive satisfaction in healthy bodily activities.

The motivation behind the accounts in this paper is to bridge the gap between a disabled and non-disabled way of learning about the world. This is not to diminish the great achievements made by those who have had to adapt to challenging disabilities, but to humanize all ways of learning and adapting. In this way, we can relate and support one another in all manners of bodily experiences.

In terms of sources, the disability cases will be drawn from Berger and Wilber’s Introducing Disability Studies as well as other individual studies done on rehabilitation and recovery. The phenomenological approach for considering the cases will be drawn from Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception and Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea and Being and Nothingness.